In the current era, we contemporary humans consider ourselves fortunate to have a much richer and more realistic understanding of what things are, what reality is, and what the natural world is about, than any of our forebears. Most of this new and developed understanding is generally attributed to the development of science, scientific methodologies, and many related innovations. While this has brought complexities with it, we are certainly in a good position for our increased understanding of the natural world.

Major steps have been taken in this regard in the broad realm of science we call physics, complemented of course by sophisticated analysis in chemistry and biology. Medical science, agriculture, building technologies, industrial production, dynamic new art forms, and so on…Additionally, these transformations in understanding of the natural world have had powerful influence in studies in archeology, anthropology, history, etc., and doubly so in the last few decades in neuroscience and neurophysics, molecular biology, quantum computing, neurophilosophy, cosmology, astronomy, and so on.

Many thinkers in earlier times wondered what the world was made of, so our great advantage is a shift in worldview in companionship with what we call natural science and the dynamic tools, experiments, devices, explorations, and constructs we have initiated and established in recent generations and decades.

We are most fortunate to live in an era in which we have begun to see actually ‘beneath the surface’ of what we commonly call phenomena or material/physical objects—this chair you are sitting in/on!

Of course, we never really say the chair is not made of wood or of textiles, or not made of foam or not made of leather, or not made of steel if indeed it is made of one, or all, of those materials, a combination of them all put together. The chair quite clearly is a material thing. The wooden leg is quite clearly a material thing; it is wood, right? I could go on.

If you told the people sitting at your dinner table with you that their chairs were not actually what they appear to be, they would wonder about you at a deep level, even though they might not say anything. This materiality, this physicality, this stuff, is the substantive component of what we call any given thing, or phenomenon, which we take to be a solid object occupying space, and in the same world in which we live, move and have our being.

Some people, on the other hand, have wondered for many years whether this stuff, the wood, the metal, the textiles, etc., is really the stuff that makes up the world,

For example, the early presocratic thinkers wondered: is there some other aspect, or manner of looking at the world, which would help us understand more fundamentally, more deeply, and in a more insightful way, what these objects, these phenomena, these physical things, really are.

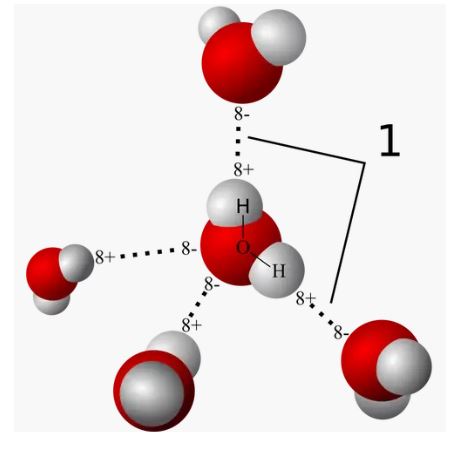

The last 150 years in the sciences have provided us with a complex world view, which is now generally accepted in the 21st century as an accurate account of the composition of things. At a simple glimpse, the idea that things, material physical objects, are constituted by smaller units called atoms and molecules. The wood, meal, textiles, of the chairs are themselves all constituted by these smaller particles.1

Many small steps, changes in conceptual frameworks, methodological and experimental tools were developed in the previous centuries to make it possible for more recent scientific efforts to show/illustrate what the atomic/molecular structure of physical objects might be.2

Analysis into component parts is a classical, scientific-conceptual procedure, and a very practical component in the worldview of what it means to understand things in the current era, from a scientific point of view. What are things constituents?

For my interest, I am decidedly uneasy in accepting that breaking things down into what we might call their component parts, is actually a full understanding of what they really are — equally important, what does this ‘breaking down’ have to do with my deep unease (angst), or my very very good espresso.

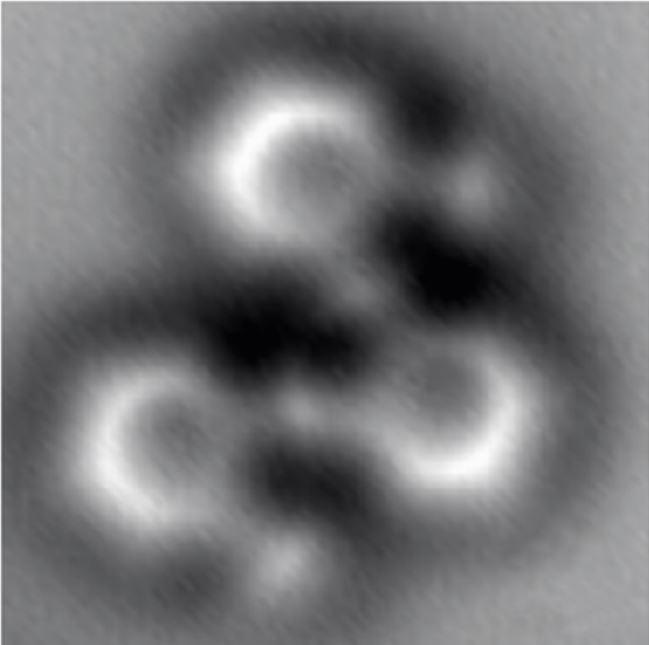

I have two areas of preoccupation: investigations at CERN increasingly illustrate that what is often thought of as matter/mass (e.g., protons) break apart into many, many, smaller ‘entities’ which themselves are not only not understood, but are also not actually things (particles, objects, matter, etc.) but are more like bundles, aggregates, and/or fields of energy. And, when I get up in the morning and go for my coffee, I am not atoms and molecules moving atoms and molecules to drink atoms and molecules, etc. I am walking, dressing, making coffee, drinking it with satisfaction and accompanied by a delicious muffin which I also made. How can that be if all the stuff is only particles and bundles of energy, pray tell?

1 Earlier thinkers had of course already had this idea, but had no way to show it, demonstrate it or put it into a larger understanding of nature (e.g., Democritus – atemnos, the uncuttable). Ongoing thinking touches on the void, infinite divisibility, the unity of the real, etc., Astonishing actually. Pretty insightful for people who thought about these things, but didn’t have our contemporary tools and worldview frameworks within which to analyze

2] brief and illustrated: matter/atoms. https://chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Inorganic_Chemistry/Inorganic_Coordination_Chemistry_(Landskron)/01%3A_Atomic_Structure/1.01%3A_Historical_Development_of_Atomic_Theory